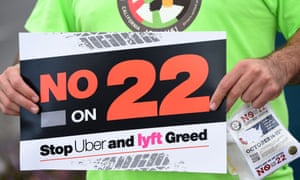

The company, along with Lyft and DoorDash, spent more than $200m to deny drivers the wages and benefits they’re entitled to.

Last week, Uber bought itself a law.

Along with Lyft, Instacart, DoorDash and Postmates, app companies spent more than $200m – the most spent on any ballot campaign in US history – to bankroll Proposition 22 in California. With its passage, the law will now exempt drivers like me from basic protections afforded to most other workers in the state.

And in the aftermath of their bought-and-paid-for victory, these companies are promising to roll out this model nationwide, foretelling a grim future for gig workers across the US.

But let’s be absolutely clear: Prop 22 is a dangerous law. Voters in California, inundated with ads promising drivers a “living wage”, flexibility and greater benefits, believed they were ensuring drivers a better future in the middle of a pandemic and recession.

But voters were hoodwinked. Drivers are now neither employees, guaranteed rights and benefits such as healthcare, nor true independent contractors, since we can’t set our own rates, choose our own clients, or build wealth on the apps.

Instead, Prop 22 promises substandard healthcare, a death sentence to many in the middle of a pandemic. We’re promised a sub-minimum wage in the middle of a recession that an independent study showed would be as low as $5.64 an hour – not the eventual $15 state minimum. We’re given no family leave, no paid sick days and no access to state unemployment compensation. Most importantly, while we’re already prevented from unionizing under federal law, the measure also makes it nearly impossible for California to pass laws protecting drivers who organize collectively, a fundamental right that companies undermine to silence worker power.

The companies fought ruthlessly to put us here. When California clarified who should be an employee for the purposes of state law, the companies first ignored it, arguing the law did not apply to them. Then, as California’s attorney general and city attorneys across the state sued them, they decided to pour millions into passing their own law, even threatening to leave the state if they did not get their way.

And when the campaign got under way, these companies were unconscionable. Uber forced drivers to click through in-app messages warning them that they would lose their jobs if Prop 22 failed – for which they were sued. It sent notifications to riders warning of longer wait times and higher prices. Instacart had its workers include “Yes on 22” stickers in every order and deliver them in “Yes on 22” bags.

They even spent part of their war chest convincing voters that it was racist to oppose the measure, a particular affront when 78% of drivers in San Francisco are people of color and 56% are immigrants. Lyft ran ads quoting Maya Angelou’s “Lift up your eyes” poem,and Uber bought billboards stating “If you tolerate racism, delete Uber” to capitalize on the Black Lives Matter movement. The Prop 22 campaign touted the support of BLM Sacramento, only to retract it when the group’s leader said she personally supported it but the group as a whole did not. All this while trying to strip a majority Black and brown workforce of fundamental labor rights.

Yet, through it all, the sentiment I’ve heard and felt from drivers isn’t resignation, but anger and energy to keep the struggle going. Drivers have been organizing before this campaign and we’ll keep organizing after, just as farm workers, domestic workers, and others cut off from basic labor standards have done for decades.

Far from ending this fight, these app companies accelerated and cemented our organizing, bringing thousands of drivers together across the state. And we have options.

First, Uber, Lyft and the other gig companies owe millions of dollars in stolen wages, for which they are being sued by the California labor commissioner. That suit can continue, along with others launched by the attorney general and several city and district attorneys, that could also give ride-hail and delivery drivers hundreds of millions of dollars in damages.

Second, these companies must keep their promises. They’ve made promises for healthcare, minimum wage, workers’ compensation and more, but in all my three years working as a driver, completing more than 12,000 rides, they’ve never followed through. Drivers will be holding them to account across the state, ensuring we are being provided the minimums in the new law.

Finally, despite threats by each gig company to take the Prop 22 model nationwide, the new administration may not be so receptive. Both Joe Biden, the president-elect, and Kamala Harris, the vice-president-elect, opposed Prop 22, speaking of an “epidemic of misclassification”, and their campaign plan specifically states they would model federal gig worker legislation on the California law, AB5, that Prop 22 is allowing app-based companies to avoid.

These multibillion-dollar companies have enough money to bring this fight to each and every state. They spent more than $200m in California, but the very next day, their stock prices soared, adding $10bn to their valuations. This is just the cost of doing business to them. Writing laws is easier than following them.

We can’t let them. In California, one of the world’s wealthiest economies, I should be able to afford rent and pay my bills as a driver. I shouldn’t be forced to scour for public bathrooms or work 70-hour weeks to do this job. But that’s what these companies have forced upon us.

Uber may have bought itself a law, but it has not bought itself reprieve. All labor has dignity, and driving for Uber or Lyft should be no different.